The Founder Transition Problem PE Buyers Miss

“The kingdom versus the crown. It’s great that you’re an incredible ruler, but you want a kingdom that’s going to outlast you.”

That’s Emily Holdman, Managing Director at Permanent Equity. And it captures the fundamental challenge every acquired company faces.

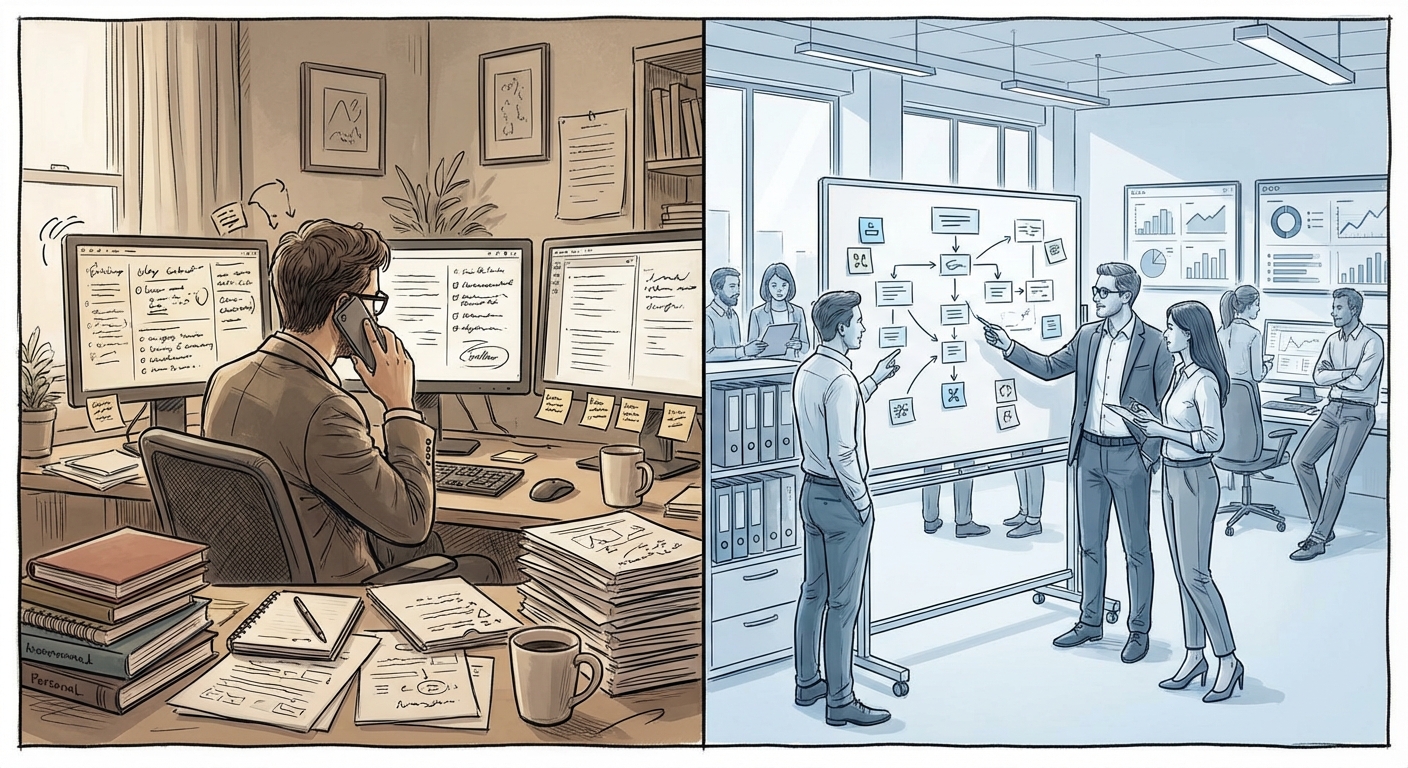

Founders wear the crown. They are the authority. They hold the relationships, the context, the history of every decision. But acquirers want a kingdom: sustainable systems that outlast individuals, documented processes that transfer, metrics that tell the truth regardless of who’s asking.

This gap creates friction from day one. If you’re the operator who just inherited a founder-built business, you’re living in that friction right now.

The Intuition Gap

Here’s a pattern that plays out across founder-led acquisitions: the business worked brilliantly for years. Revenue grew. Customers stayed. The founder knew exactly what was happening.

Then the deal closes. New ownership asks basic questions: What’s driving revenue by segment? Where are we losing margin? Which accounts are at risk?

And nobody knows. Not because the founder was hiding anything. Because they never needed to know it that way.

Imagine acquiring a $30M business with solid fundamentals. Month two, you want gross margin by product line. The ERP exists, but nobody’s pulled that report before. The founder knew which products made money because he’d been pricing them for 25 years. Or consider a services business where the founder personally managed the top 20 accounts - knew which clients were flight risks, which ones would pay premium for faster turnaround, which sales reps needed coaching. All of it lived in his head. None of it transferred.

John Caple, Partner at Hidden Harbor Capital Partners, describes this dynamic: “Founder’s really good, but they do what I call managed by walking around. They started the business. They know every employee, they know every customer. They don’t need systems and reports. That works really great up to a certain size and in one location.”

The founder could answer any question because they were the system. But managed by walking around has a ceiling. It scales to one location, maybe two. It survives one founder, but not a transition. And it provides zero visibility to anyone who wasn’t there from day one.

Why This Becomes a Crisis Post-Acquisition

The transition from founder-led to system-led isn’t optional after acquisition. Three forces make it mandatory.

New owners need data, not stories. PE boards don’t run on gut feel. When the board asks why Q3 missed plan, “I talked to the sales team and they feel good about Q4” doesn’t cut it. Carl Press, Partner at Thoma Bravo, makes the stakes clear: “If we’re not keeping score, we’re not going to see problems early enough. We’re going to see them too late. So we want to see the leading indicators.”

Founders saw problems early because they were embedded in the business. New leadership doesn’t have that advantage. Without systems that surface leading indicators, you’re flying blind until the lagging indicators hit the P&L.

Integration requires handoffs. Acquisitions bring change: new leadership, new reporting structures, new strategic priorities. Every change requires a handoff. Handoffs require documentation.

When the head of sales retires and you need to onboard a replacement, what’s the ramp plan? What does the territory map look like? Which accounts have relationship history that matters? If the answer is “ask Steve, he’s been here 20 years,” you don’t have a process. You have a single point of failure.

Scale demands repeatability. The thesis behind most acquisitions includes some version of “we’re going to grow this.” Growth means new markets, new customers, new hires. Everything the founder did by instinct needs to become something others can execute.

James Sidwa, Managing Partner at Heartwood Partners, puts it simply: “Failure to plan is planning to fail.” In founder-built businesses, the founder was the plan. Now you need the plan to exist independent of any individual.

The Real Problem: Nothing Is Wrong

Here’s what makes this transition difficult: the founder didn’t do anything wrong.

Managing by walking around worked. The relationships held. The tribal knowledge served the business well for years, sometimes decades. The practices that now create friction were once the company’s competitive advantage.

Emily Holdman offers perspective: “We’re all messy, and businesses are just collections of people. Businesses are messy. And leadership teams are messy.”

The founder’s approach wasn’t a failure. It was appropriate for the stage. But stages change. What got the company here won’t get it where it needs to go.

This is where deal assumptions and operational reality diverge. Diligence validated the numbers. The model worked. But nobody stress-tested whether the business could operate without the founder’s intuition holding it together.

Building the Kingdom: Where to Start

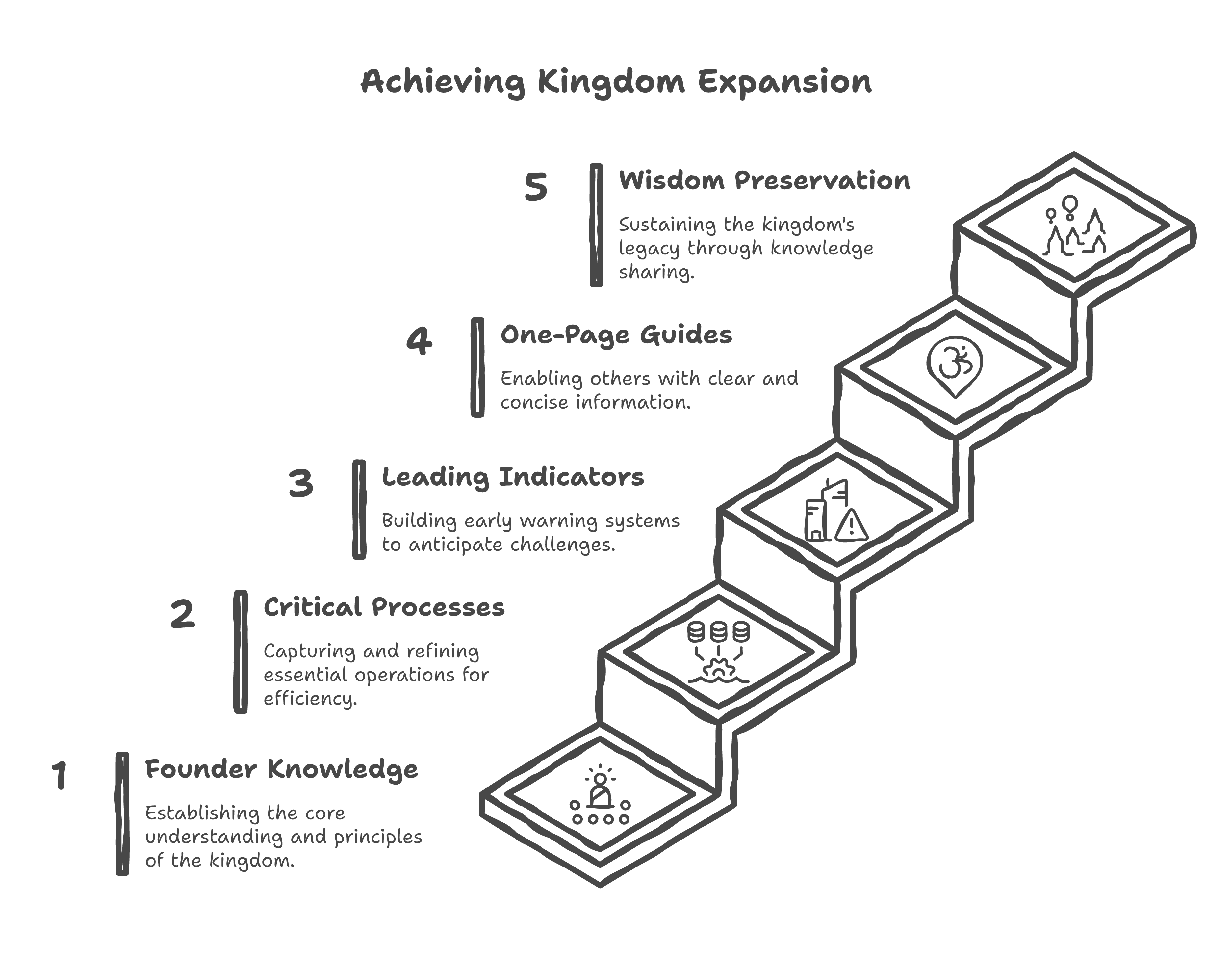

The shift from crown to kingdom isn’t a single project. It’s a series of decisions about what to systematize first.

Start with critical processes. Ask yourself: What would break if the person who owns it left tomorrow? That’s your starting point.

For most companies, critical processes cluster around customer relationships, financial close, and operational execution. The sales pipeline. The monthly reporting cycle. The fulfillment workflow that everyone just knows.

Identify the metrics that drive the business. Founders often know intuitively which numbers matter. They track them in their heads or in a personal spreadsheet nobody else sees. Your job is to surface those metrics and make them visible.

This isn’t about dashboards for the sake of dashboards. It’s about answering one question: What are the three to five leading indicators that predict whether we’ll hit plan? (If you’re not sure where to start, an analytics maturity assessment can help identify the gaps.)

Revenue is a lagging indicator. By the time you see it, the work that created it happened months ago. What are the early signals? Pipeline velocity. Customer retention rates. Production yield. Whatever drives your specific business.

Document for transfer, not compliance. Every process you document should answer one question: Could someone new execute this without asking the person who does it today?

Good process docs capture not just the steps but the decisions: Why do we do it this way? What breaks if you skip this step? What does good look like?

Preserve the wisdom. The founder’s intuition wasn’t random. It was built on pattern recognition from years of experience. As you systematize, capture the why behind the what.

That weird rule about never discounting for clients in certain industries? There’s probably a reason. Maybe those clients churn faster. Maybe they demand more support. The founder knew this from experience. Your job is to extract that knowledge before it’s lost.

The Messy Middle: What to Expect During Transition

This transition doesn’t happen in 90 days. It happens over months, sometimes years.

You’ll have conversations where founder-era leadership feels like you’re criticizing how they ran the business. You’re not. You’re adapting successful practices for a new context.

You’ll build systems that feel like overhead until they prove their value. The first time a documented process catches an error that would have slipped through the old way, you’ll see the return.

You’ll discover that some of the founder’s intuition was right in ways you didn’t understand. Not every “we’ve always done it this way” is resistance to change. Some of it is hard-won wisdom that takes time to surface.

The Stakes: What Happens If You Don’t Make the Shift

The companies that make this transition look different two years out. They have visibility into performance that doesn’t depend on any single person. They can onboard new leaders without losing momentum. They can scale without scaling chaos.

The companies that don’t stay stuck. They remain dependent on founder-era knowledge that erodes over time. They can’t answer basic questions without archaeology. They react to problems instead of anticipating them.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most acquisitions assume this transition will happen. The value creation thesis depends on it. When it doesn’t happen, the deal underperforms - and the operators who couldn’t make the shift bear the consequences.

The business that existed before close - the one that ran on founder intuition - isn’t the business the deal model assumes. The gap between those two versions is what you’re managing every day. The faster you close that gap, the better your outcomes.

One Question to Ask Yourself

If you left tomorrow, what would break?

Not what would be inconvenient. What would actually break? Which processes only work because you’re there to make judgment calls that aren’t documented anywhere? Which relationships only function because you hold context that hasn’t been transferred?

That’s your starting point. That’s where the kingdom begins.

If you’re navigating the transition from crown to kingdom, that’s exactly the kind of work I do. Reach out.